ERNIE ELLIOTT

Power to Spare

Ernie Elliott: A Master Engine Builder

By Ben White, special to ERH

Among the most accomplished legendary engine builders in NASCAR history, only one is synonymous with north Georgia and the state’s most famous family of racers.

He is Ernie Elliott, the man behind the power and dominance of younger brother Bill on short tracks and superspeedways in NASCAR’s Cup series in the 1980s and 1990s.

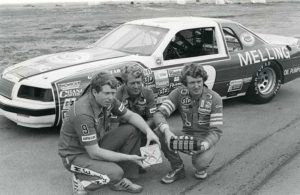

The highly respected engine builder and crew chief received much recognition while working for Elliott Racing and Melling Racing three decades ago, including Engine Builder of the year in 1985, and Engine Builder of the Decade for the 1980s.

Ernie’s love for race engines began at a young age after joining his father, George Elliott, during trips to the relatively new Daytona International Speedway in the early 1960s. The deep baritone sounds they produced at full song played like music to his ears. As a teenager, Ernie worked in his family’s building supply business and also sold race car parts out of a delivery van he drove to various race tracks.

George, a former school teacher and principal turned businessman, taught his sons many lessons about life and emphasized doing things the right way.

“He was tough but fair,” Ernie said. “He expected things to be done a certain way. He wanted you to think for yourself and think on your feet. He expected us to be successful and learn the lessons of life through hard work.”

From the days of building junkyard jalopies, Ernie was fine with not being the race driver in the family. His passion was giving the cars the power they needed to win.

“I had built chassis, but I preferred engines,” Ernie said years ago in NASCAR Illustrated magazine. “It came much more natural to me to do the motors. I don’t know for what reason, but it just came more natural to me. I was interested in what created the power and the fact there were so many moving parts that had to work together without coming apart.”

By the mid-1970s, Bill was a consistent winner at Boyd Speedway in Chattanooga, Tenn., Middle Georgia Speedway in Macon and their home track, Dixie Speedway in Woodstock, Ga. His natural talent behind the wheel prompted George to buy a single Ford Torino to field in select NASCAR Cup series races beginning in the fall of 1976. Little did he know that over time, sons Ernie, Dan and Bill would build one of the most storied race teams in all of motorsports.

By the mid-1970s, Bill was a consistent winner at Boyd Speedway in Chattanooga, Tenn., Middle Georgia Speedway in Macon and their home track, Dixie Speedway in Woodstock, Ga. His natural talent behind the wheel prompted George to buy a single Ford Torino to field in select NASCAR Cup series races beginning in the fall of 1976. Little did he know that over time, sons Ernie, Dan and Bill would build one of the most storied race teams in all of motorsports.

“We went to Atlanta and Talladega in 1976 and qualified well,” Ernie said recently. “We were as good as anyone. I built the engines and Bill worked on the chassis. He could do anything with the car. We all had areas we were good at so we could be the best we could be. We all had successful careers.

During 23 seasons of Cup Series racing spanning through 1999, Ernie’s engines have set many milestones, including a Cup series qualifying record of 212.809 mph, set by Bill at Talladega Superspeedway on April 30, 1987. Ernie was also instrumental toward winning the 1988 Winston Cup title with Bill and team owner Harry Melling as well as 51 Cup poles, 39 wins, 148 top-five finishes and 291 top-10 finishes. He has also built 37 race-winning ARCA engines for three ARCA champion-winning teams. The majority of Ernie’s wins have been with Ford but some have come with Chevrolet and Toyota engines over the past decade.

To this day, Ernie still has a passion for building the most powerful and reliable race engines possible.

“I’ve always loved engines from the time I was a kid,” Ernie said. ”I’m not really the kind of person that wanted to work for someone else, even though I did work for the post office once. We had success in the sport that came through a tremendous amount of hard work. I wouldn’t change anything.”

Archive: Winston Cup Illustrated

Interview by Steve Waid

The rise of Bill Elliott to NASCAR Winston Cup superstardom has become one of the great success stories in racing. Yet even the 1988 Winston Cup champion would admit the story is incomplete without a documentation of the career of his older brother, Ernie.

That has been difficult.

Considered by many to be a brilliant racing engineer whose contributions to his brother and Melling Racing can’t be measured, Ernie Elliott is nonetheless a man who shuns the public. He does so not because he is a recluse; rather, it is simply his way.

Although always a target for the media, he has seldom been hit. Instead, he has gone about his business while his brothers Bill – always in the spotlight – and Dan meet the press.

Although always a target for the media, he has seldom been hit. Instead, he has gone about his business while his brothers Bill – always in the spotlight – and Dan meet the press.

As a private person, Ernie Elliott has sometimes been called hostile. But those who know him best say that is not the case. He is intense about his work and protective of his personal life. There’s always a job to do at the track and in the shop and when the job is complete, it is time for family. Then it’s time to do the next job.

Ernie Elliott has been with his brother through every step of their racing careers. They were nurtured in racing by their father George and working closely with him, they made their start in Winston Cup competition in 1976.

By that time, it has long been established that Bill was the driver and Ernie the mechanic. Able to handle all manner of responsibilities, Ernie soon found himself gravitating toward engines.

As Bill developed as a driver, Ernie made gains as a crew chief, which, logically, became his job as the Elliott’s began to compete in Winston Cup racing. More importantly, however, he matured as an engine builder.

Rescued from oblivion with the financial assistance of Harry Melling in 1981, the Elliotts became employees, consultants, partners and virtually anything else you might care to mention when Melling, a Michigan businessman who directed Melling Auto Parts among other enterprises, bought Elliott Racing in time for the 1982 season.

In 1983, Bill Elliott won his first career Winston Cup race. There were three more victories in 1984 and then came the astonishing 1985 season, when he won 11 races, 11 poles and The Winston Million.

That season forever changed the Elliott’s. Gone was their “country boy” image. Gone was the lack of attention from the press and public. They were celebrities and while they might not have wished to be, there wasn’t a thing they could do about it.

Bill was thrust into a new role. He was constantly in demand. Ernie remained virtually unapproachable but nevertheless, he felt the strain and pressure created by the overwhelming success of ’85.

The year did not end with a championship, however. So there was another goal to attain. It came in 1988 when Bill won the title by 24 points over Rusty Wallace. It was decided at the last race of the year, the Atlanta Journal 500 at Atlanta International Raceway, where Wallace was dominant and won easily. However, the Elliott’s came into the race needing to finish only 18th or better and wound up 11th after a conservative run.

That prompted more criticism, in that many thought a champion should charge to the checkered flag like a mounted cavalryman with his saber. There was once a time when Ernie would boil inwardly over such treatment, but today he is a mellower man. By his own admission, “I don’t pay it any attention.”

In Dawsonville, Ga., the Melling Racing complex will soon house 70,000 square feet of shops. A good portion of that will be devoted to engines, as Ernie has overseen the placement of one of racing’s best motor production, research and development facilities.

With the passage of time, Ernie Elliott has changed. But not a great deal. He may be more forgiving to critics and more accessible to some members of the media, but he is every bit as intense a perfectionist as he ever was. He maintains a strong drive to succeed, even though he and his brother have carved their names into racing legend.

There has been an extensive interview with Ernie Elliott. There has now. In his lengthy talk with Winston Cup Illustrated Executive Editor Steve Waid, the man who many say is the main cog in one of the most celebrated racing operations in history reveals more about himself, his philosophies of life and his chosen profession that has ever been presented at any other time.

WCI: Let’s go back to the beginning. It would be safe to say that it began for you as a teenager when you spent a lot of time working with out father in various businesses. Would that be right?

ELLIOTT: I worked mainly with the building supply business. I would haul lumber, stuff like that.

WCI: But he was already in racing, right? In fact, he’d been in racing for just about as long as you could remember.

ELLIOTT: Daddy and his first cousin had been racing since, oh, I guess 1959-60, somewhere in there. They fooled around with Sportsman and Modified cars. They had an old Studebaker they took to Daytona.

WCI: Was it simply a natural progression for you and Bill to get into racing, then?

ELLIOTT: Well, I guess. There was a fascination there for us that I think just led us in that direction. That’s the way it was for us.

WCI: Did you have a car in high school, one that you worked on and tooled around town in?

ELLIOTT: Yeah, but neither Bill nor I tooled around town too much. We pretty much worked. We didn’t have a lot of free time.

WCI: Well, you were a couple of growing boys. You have been portrayed as the extremely serious type, but you must have done a few things to have some fun.

ELLIOTT: We worked. We worked for fun. That was about it.

WCI: You have expressed the opinion that Bill had the natural ability to drive and that you never had it. Is that correct?

ELLIOTT: My patience isn’t that long. Bill seemed to have a good high level of concentration. He has it today. He can sit there for a long period of time and wait for things to happen. He waits for situations to come to him. I can’t do that.

WCI: When did you first run a race car together in a joint venture?

ELLIOTT: It was in 1973. That was the first time Bill drove. He drove in only a few races. In 1974 and 1975, he ran a lot more races. We ran races at Dixie Speedway, an asphalt track, and we ran a few times at the old Chattanooga (Tenn.) Speedway, I think it was called Boyd Speedway, and we ran a few at Middle Georgia Speedway which was down in Macon. Dixie Speedway was in Woodstock (Ga.) and that was our home track.

WCI: And did it just naturally evolve that you became the engine builder?

ELLIOTT: I had built chassis, but I preferred engines. It came much more natural to me to do the motors. I don’t know for what reason, but it just came more natural to me. I was interested in what created the power and the fact there were so many moving parts that had to work together without coming apart.

WCI: It was your father’s decision to go into Grand National racing – now Winston Cup racing – in 1976, right?

ELLIOTT: Yes. Daddy made the decision. Bill and I disagreed with him. We thought it was too early. We felt like we needed more experience on short tracks. But when you look back, it was the best decision because we were able to start our learning process at a much earlier time. If we had waited three or four years, we might not have ever run Winston Cup. Things would have been so different. Things would have been more expensive. I don’t know, we might have been more successful. We might not have been. Who knows?

WCI: But it was true that in 1976, it was more economical to venture into big-time racing.

ELLIOTT: It was more economical to run then that it was at a later period. As all of us know, the cost of racing really started increasing in 1980, 1981,1982, along in there. Every year after that, costs really have increased. So for us to begin in 1976 was a very practical thing economically, now that I look back on it.

WCI: You’ve said that your first Winston Cup engines weren’t good…

ELLIOTT: They were terrible, absolutely terrible. Nothing could have been much worse.

WCI: That’s getting pretty down on yourself. But it’s true you were just learning.

ELLIOTT: Well, that’s true. But the main thing was we ran good on short tracks. We didn’t see how it could be that much different when it came to engines. But we got our eyes opened. But that was good because it put things into perspective. We knew where we stood. We knew we had a lot to learn. It humbled us a little. It made us work harder to achieve our goals. I think it was good in that perhaps we might not have worked as hard if we had come in and started running good right away.

WCI: With such humble beginnings, you knew how far you had to go and what you had to do to get there.

ELLIOTT: We didn’t know how far we had to go, really. But we knew we had a long way. Let’s put it that way.

WCI: And from the start, as a team you were on your own.

ELLIOTT: Basically, we were. We learned on our own. I guess one of the biggest things that helped us was when we bought a couple of race cars and a good deal of engine parts from Roger Penske in late 1977. That gave us some more insight into what parts were being used in some of the areas where we were going wrong.

WCI: As you look back on it today, do you see yourself growing and improving as an engine builder with each year of the team’s development through the early years?

ELLIOTT: Yes. Every year we got better. But it was all a matter of experience. We gained more. But we made more mistakes and learned from them. As we raced more, we obviously made more mistakes. But they helped. We tried to always look at what we were doing – especially on motors – and we always tried to do a better job. As the finances got better, we were able to do different things and have different pieces to work with that broadened our knowledge as to what was going on with motors.

WCI: With all of the short-track experience you and Bill had, why did the Elliott’s become so proficient on superspeedways so early instead of things happening the other way around?

ELLIOTT: I don’t think we had that much short-track experience. We had a good deal and we learned most of what we knew there. But it still wasn’t a lot. After we ran some in Winston Cup, we reversed it and learned a lot on superspeedways. I think it shows today. Bill isn’t a beat-and-bang driver. He doesn’t get in there and slam it out. He never did on short tracks. He was a clean runner, with no gouging or beating or banging. He’ll do it when he has to, but you just don’t see him doing it often. The way you race on the superspeedways, where you don’t lean on each other and beat and bang, that was more suited to Bill’s style. So we just felt more comfortable on the bigger tracks. That was a big factor.

WCI: In spite of your continued growth during the early years, it reached the point where you could see the finances running out, largely because you didn’t have a major sponsor. But things began to change. Just when?

ELLIOTT: In 1981. In late 1980, we went to Michigan to talk to two people, Harry Melling and another guy. They each offered us deals. Harry’s deal was just about half for the whole season what the other guy offered for one race, the Daytona 500 of 1982. It was fortunate for us that we didn’t look at the money aspect. We looked at what made good business sense. We were looking at Harry for a lot less money, but we were looking at a long-term relationship. And that’s what it turned out to be.

WCI: You were involved in those negotiations?

ELLIOTT: Yes

WCI: Now, to take half the proposed money in favor of a long-term relationship must mean you felt such a relationship to be extremely important in racing.

ELLIOTT: I think it’s the most important thing in racing. In order to be successful in any way at all in this sport, or in any business for that matter, you can’t have short-range thinking. You’ve got to have long-range goals. Right now in this business, we have a five-year plan and we’ve had that pretty much intact since we started racing. When we spend one year, we tack a year back on the end of it so we’re always thinking about where we want to be in five years. Our deal with Coors, our deal with Melling, our deal with Ford – everything we’ve done has been established for a long period of time. And there have been relatively minor changes.

WCI: Does that help a team to know that things will be in place for a long period of time? Obviously it must help to know you won’t be renegotiating contracts every year or so.

ELLIOTT: That’s where the family aspect comes in. In our situation, we all have money in the team. It’s not a situation where the driver can up and say, “Hey, I’m going somewhere else.” There’s also a situation where the employees feel more comfortable. It’s very hard to do a job in an unstable situation. It’s hard to concentrate on what you are doing when you are wondering where you’re going to be the next year. It’s hard to tell your employees to do a good job when no one knows where the heck they’re going to be in the coming year. I think the situation we’ve got promotes a lot of stability as far as employees and sponsors are concerned.

WCI: History shows us that the Elliott’s, as a team, improved with each passing year and ultimately became a major success. But during the evolution, could you, as crew chief, see it all coming?

ELLIOTT: Yeah, we always felt we were better each year. But then there’s this: Even when we won our first race at Riverside, Calif., in 1983, we still didn’t have winning race cars. We had a third or fourth-place race car at Riverside. We’ve just tried to be realistic over the years about our chances for winning and about performance on the race track. I come home and evaluate each race to try to get some kind of idea about our performance level.

WCI: So you’re saying that even if you win a race, you might evaluate the performance as say average overall?

ELLIOTT: Yes. But I usually don’t have “average.” I usually have “good” or “bad.” The main reason I spend the time evaluating races is so I know what changes to make in order to improve our performance. I think you’ve got to do that.

WCI: You’re like a coach who looks at perfect season and says, “We were lucky. We didn’t have all that much talent.”

ELLIOTT: You can look at it that way. But the thing you’ve got to do is that you have to be totally objective when you evaluate each race. You have to look at the total picture. When I evaluate, I can basically rerun every lap we ran on the track. I try to get an overview. For example, in 1985, there were a lot of races we won but I can say that from objective evaluation, we certainly didn’t have the best race car every time out. Sometimes we had far from the best race car.

WCI: In 1985, you had a remarkable season. As you say, there might have been times when you won races yet didn’t have the best race car. But there were other times when clearly you did have the dominant car. Races at Talladega and Daytona come to mind. Do you feel particularly satisfied when you win and have the dominant car at the same time? Is that your goal every time out?

ELLIOTT: Well, it depends. It depends on how good I think all the other competitors are. I evaluate that, too. I try to determine how good everyone else is. You’ve got certain key cars you can rate in each race. If you clearly win a race and those others had problems and simply didn’t run as good as they could have, then you’ve got to rate your performance accordingly. You have to rate it according to how good you feel the others could have been. That’s the only way you can get better. To me, that’s just being realistic. You aren’t deluding yourself.

WCI: So even if you have a strong car and win, you can still reach down into yourself and say that it wasn’t as sweet as it could have been because the others, the ones you had to beat, simply didn’t perform up to their potential?

ELLIOTT: Yes. To win like that, well, it would be almost like taking an NFL team and going up against a high school team. Obviously, it wouldn’t be that drastic, but you get my point. In a lot of cases, we go to races where a lot of good cars have problems and are not capable of performing up to their high levels. You always have to realize that and evaluate accordingly. It projects a clearer picture when you do that and it keeps your mind on who you’ve got to beat the next time around.

WCI: As mentioned, 1985 was a great season. You had 11 superspeedway wins and you won the Winston Million. That was a pressure-filled season, no doubt. It was especially tough on Bill because it brought him out. He was constantly in the public eye. It was new for him. It was new for the team, too.

ELLIOTT: That’s right. I would say that 1985 was a good and bad year. We won a lot of races but we did a lot of things wrong. I don’t think we conducted ourselves as well as we could have in a personal sense.

WCI: In essence, then, would it be fair to say that if it was tough to Bill to come into the public view, it was twice as hard for you?

ELLIOTT: It was hard for all of us. I don’t think any of us, and that’s anybody on the team, knew how to contend with it. We had never been the focus of attention and suddenly we were put into a position where we were the focus of all the attention. Not just some of it, but all of it. It just created problems for us – problems we had to overcome. It was all a learning experience, now that I look back on it. I’ve said more than once that I personally learned a lot from the 1985 season and I think everyone on the team did as well.

WCI: Given your rating scale, even when you won the Southern 500 of 1985 to earn the Winston Million, you wouldn’t have rated your car the best, correct?

ELLIOTT: No, I wouldn’t have. It was far from the best race car. We simply built the car to last the race. We built it to finish if at all possible; that’s what we were trying to do. At best, it was a fifth-place car. But as circumstances turned out, we were fortunate. We had decided that after the Coca-Cola 600, where we could have wrapped up the Winston Million, we were going to do things differently. We had brake problems at Charlotte, but that alone wasn’t the problem. We made a lot of mistakes; mistakes brought about because we simply weren’t ready to run that race under the kind of pressure we were experiencing.

WCI: No question, there was pressure at Charlotte.

ELLIOTT: People tend to look at it and say, “Well, it was just a race..” That’s true. It is just a race until you look at that $1 million. That’s pressure. And it’s not only pressure from that, but other sources as well. For us, we had even more pressure because we had won so many races up until that point and people just expected us to win.

WCI: So at Charlotte and again at Darlington, the Elliott team is squeezed by pressure from two sources: First, there’s the $1 million and second, it is such a hot team that it is expected to win every time out. Is that right?

ELLIOTT: Yes. It made all of us tense. At Charlotte, we didn’t really admit to the pressure. But it was there. After Charlotte, after we lost because of our mistakes, we realized there was pressure. We came to Darlington knowing this. That didn’t make things easy, but it did make things easier, if you know what I mean. We were more careful to do things because we admitted there was pressure. We came to Darlington to finish. We had to finish. That’s the way we had to view it. Out objective, obviously, was to win the $1 million. I can’t deny that deep down inside that’s what we wanted to do no matter what we told everyone else. There’s no question that if we didn’t win it, we would have left feeling bad, feeling remorse. It’s just natural.

WCI: You’ve said you had a fifth-place car in that race. But your goal of finishing seemed to work out perfectly. Dale Earnhardt had a strong car and hit the wall, so he was virtually eliminated. Harry Gant had a strong car and had problems. And then there was Cale Yarborough. He was leading Bill late in the race when he lost his power steering. When that happened, what were your feelings as you saw it develop?

ELLIOTT (Laughs): Shoot, the way that race was going I didn’t feel anything. If there’s one thing I’ve learned about races, until you take the checkered flag, it ain’t over. All it would take would be one little mistake and that would be it. It could be the pit crew or the driver. Just one little mistake.

WCI: So even though Bill took the lead, things didn’t ease up for you.

ELLIOTT: Not really. Yep, it would be safe to say that things didn’t ease up. But when he took the checkered flag it felt great. The pressure left. Well, it really didn’t sink in, I guess. You get so hyped up for a race… I think in a situation like that, it really takes a few days for it to sink in; for you to realize what you have accomplished.

WCI: But after that, there was the business of the championship. You were up against Darrell Waltrip and had a lead of more than 200 points following the Southern 500. You have said that you guys had to learn to win a championship, just like everyone else. In 1985, you got an education.

ELLIOTT: We simply didn’t know what it took. All that stuff bout the championship that was written back then said that Darrell won the championship. True, he did. But he didn’t take it from us, we gave it to him. We basically made it a gift. There were mistakes we made. Had we known how to win a championship then, we would have probably won it back then, given the point lead that we had. It was obvious we didn’t know how to win it. We didn’t know how to attack the pressures and Darrell’s guys were awfully good at the ‘psych’ jobs and such. Stuff like that does affect your performance. But it wasn’t that as much as the fact we didn’t know what it took to win a championship. To clarify that, we didn’t put very much stock in short-track racing and that is clearly an area where we should have applied more work. That was our fault. But we’ve learned from it.

I have to say that a lack of short-track strength was the single biggest factor in our losing the championship. In all the short-track races, we just ran terrible You can go right down the list and see for yourself.

WCI: Would you agree that your intensity level as a team over the last few months of the season decreased after you won the Winston Million?

ELLIOTT: Oh yeah, I would think so because… anything that you do, you are building toward a level in which you continually have to psych yourself up. The adrenalin flows. You are going toward one main goal. Once you achieve it, you are pretty much burned out. I would think that was one of the biggest things that hurt us in the championship. But when you look back at it, the Winston Million was our ultimate goal. When you compare that to the championship, it was worth a lot more. If I had to do it all over again, if I was put in the same circumstances this year that we had in 1985 where we were able to win either the Winston Million or the championship, it would be a hard decision to make.

But I’ll tell you, there’s something special about the Winston Million. You’ve only got four races to do it in. To win the championship, you’ve got 29 races to do it. I just think there’s something special about the Winston Million. You have to win on the race tracks which over the years have proven to be the hardest to win on. Prestige is one part of it, because these tracks and their races clearly carry the most prestige. I think if I had to do it all over again, if I had a choice, I think I would look at the Winston Million over the championship.

WCI: There was much discussion about your team and its performance in 1985. The way Bill was running, people – competitors and fans alike – were offering reasons that varied from special parts to downright cheating. There was a lot of talk. But since, it has come out that it really wasn’t one individual thing.

ELLIOTT: Oh yeah, we were doing everything, if you listen to how other people talked. We simply worked good as a unit. We had a lot of luck, that was one of the biggest things. We were very fortunate in several races. I think I can count five races we won in which we were not even remotely the best race car.

WCI: How did you take all the talk that went on? Did you shrug it off? Did you think it was funny?

ELLIOTT: In 1985, it bothered me. But after 1985, which was a big learning year for us as far as things like that go. Well, things like that just don’t even bother me any more. Now, I just don’t pay any attention. I don’t even read the stuff in the papers. I honestly don’t read very much at all. I just don’t have all that much interest in reading about racing. It’s a business.

WCI: You raced well through 1986 and ’87, although they weren’t remotely close to the kind of year your team had in 1985. Then came 1988, when you won the championship. Again, there was pressure, right on down to the last race of the season in Atlanta, though, you were a seasoned team and you had options. That was a big difference, right?

ELLIOTT: Yes. In a lot of ways, 1988 was a lot like running for the Winston Million. To win the championship in 1988 would be the high point of the year for us. I think everyone stuck together and worked hard for it. We had the point lead going into Atlanta. We knew where we had to finish. One thing I should say about that is that you’ve got to look at statistics. In any race you go into, especially when there’s as much at stake as there was for us in Atlanta in 1988, you’ve got to know the statistics. If you take Ford’s statistics in Atlanta, you’ll learn that they’re not very good. We won at Atlanta and other Ford drivers have won at Atlanta. But there have also been some terrible races for Ford at the track. Now, I’m running Fords so I have to look at Ford statistics. We went into the race knowing where we had to finish and knowing Ford’s record at Atlanta. That led us to the conclusion that we weren’t going to run very hard. A lot of people disagreed with that, even today, but they don’t pay the bills. The revenue that comes from racing pays the bills so we made a business decision. To me, racing is a business. It isn’t a sport anymore.

We stuck to our decision at Atlanta. If I had to do it again tomorrow, I would do the same thing. We didn’t run hard at all. Rusty Wallace won the race, but we came home 11th and won the championship. If they told me tomorrow that our car had to finish 30th to win the championship, then I’ll tell you what – our car wouldn’t run very hard. People can call that stupid if they like. But it is what is going to work. Look back at 1989. At what point did Dale Earnhardt lose the championship? Did he lose it because he fell out at Charlotte (in October)? Did little things cause it? What was the main key? Those are things you always have to look at, especially when you are in a position to win a championship in the last race of the year. You could very easily be the first car out of the race.

WCI: In 1988, despite the championship, you caught some heat from the fans and even the media. But bases on what you’ve said about your decision, you simply had to absorb that, then?

ELLIOTT: That’s right. You know, if you take the 1988 season versus the 1985 season, the difference in 1988 is that basically we just didn’t pay any attention to what was said. It was no big deal. We knew what we had to do. When it gets to be a situation where you let other people dictate what you are going to have to do, then you aren’t going to be very successful. You’ve got to be able to make your decisions, make you game plan and thick to them, regardless of what everyone else does. Rusty, in 1988, did everything he had to do in Atlanta. He won and clearly dominated the race. That’s what he had to do. Well, we did what we had to do. And when it came down to the final race of 1989, Earnhardt did to Rusty what Rusty had done to us the year before. Earnhardt did exactly what he had to do. Rusty did too.

WCI: Considering the 1988 season then, would it be fair to say that winning the championship would have been much more difficult, if at all possible, if you had learned the lessons of 1985?

ELLIOTT: I think so. I know it would have. Every year we’re involved in racing, we learn. I think that’s clear for all the people who are in the sport right now. You go through your periods of everyone liking you and then not liking you because of things you do. Darrell Waltrip had been through it. He’s been through the times when no one liked him and now everyone does.

WCI: How about you personally? How have you changed? Are you more open than you once were? As far as interviews go, you were once a tough nut to crack.

ELLIOTT: Well, I don’t know… I think the way things are, all of us will continue to open up. I think it’s a situation where we have all learned from the past. In 1985, I ran virtually all aspects of the operation and it’s very hard to keep your mind on all that stuff. It doesn’t make you an easygoing person. It’s hard to put up with distractions.

WCI: You once said you wouldn’t mind if the press was kept out of the garage area. Do you still feel that way?

ELLIOTT: I think the media, over the past few years, has changed. I’ve changed in the way I view the press. And I think the media has changed in the way it views the sport now. That’s continuing to change. Early on, the media didn’t seem to know much. There was no “media tour,” for example, where the media could learn. Now you’ve got it and it’s very good. The media is able to come around to the shops and see what goes on inside the facilities. Now the media can learn what takes place not only at the race track, but what it takes to get there. I think now all of us are getting a clearer understanding of what each of us does. Relations between the workers like myself, the drivers and the media are becoming better as we all become more informed. We have a much more knowledgeable media now than we did several years ago.

The one thing about the media that I criticize is their criticism of the sport. We don’t need to be critics of the sport. We represent multimillion dollar corporations that don’t want bad publicity. There are situations that arise from time to time that are uncomfortable, like the situation between Earnhardt and Ricky Rudd at North Wilkesboro (N.C.) last October. Let’s say everything got blown out of proportion because as soon as it happened, the media was right there. It would have been much better if the media had restricted itself to a single post-race interview with Earnhardt and Rudd. Then there would not have been bad statements made over live TV. I think certain situations arise where, and I’m speaking for all of us as competitors, we could bite our tongue harder if a microphone was stuck to our face. We need a clear head to answer a question.

It’s the media’s responsibility to look at certain situations and admit that they could be potentially damaging and wait five minutes or 10 minutes. Maybe the results aren’t as sensational, but what are we selling here? As we know, the sport has been good to all of us because of the involvement of large corporations. It’s even been good for the media. A lot of the companies advertise a great deal with publications and on TV, right? Like in Winston Cup Scene. I think it’s a situation where we all owe it to ourselves to be a little more cool-headed when situations arise. I don’t know if everyone agrees with that, but it’s the way I feel.

WCI: You are in effect saying that you want the media to be as responsible in their jobs as you are in yours.

ELLIOTT: Right. I think in the past year, things have evolved into a much more workable situation. Everyone makes mistakes. If you do a job, you’re going to make a mistake. You are going to do something wrong. I make more than my share. But I still feel that in the area of media relations things are improved because for the most part, everyone is more informed than they were several years ago. My biggest beef is a lot of criticism. I don’t think racing needs criticism and controversy to draw spectators or sell papers. If the level of competition stays high and the level of exposures increases, there will be plenty of places to sell papers.

WCI: In 1989, the team got off to a rough start. Bill broke his wrist at Daytona and he repeatedly said that the injury caused a decrease in his input and thus negatively affected the team. Isn’t it true that Bill’s lack of input was a problem, but figuring out the 1989 Ford Thunderbird was an even more critical problem?

ELLIOTT: Our season wouldn’t have been nearly as bad if we hadn’t gone to a completely new body style. If we had continued to run a body style like the 1988 Ford, we would have had a more reasonable chance for the title. In 1989, we were in a rut and about the time we figured we had dig ourselves out, we would fall right back in again. We never got a clear shot in 1989 and I feel we were very fortunate to win the races we did. I’de just as soon put a big “X” over 1989.

WCI: Did you sense the irony of 1989, when Rusty was forced to make decisions at the last race of the year in an effort to win the title, and then making the same decision for which he criticized you in 1988? In other words, he chose to be conservative just as you did in ’88 and he criticized you for that move.

ELLIOTT: I thought it was pretty interesting (laughs). I thought it was interesting the way he ran the race. Obviously from the way he talked he shouldn’t have run the race that way. But I think Rusty learned a lot from 1988. We’ve got to make mistakes to learn. We’ve got to open our big mouths and stick our big feet in them. We have to learn so that the next time we don’t open our mouths quite as wide and stick feet quite as big in them. He knew he had to run that Atlanta race differently than he did in 1988. The thing he did do was swallow his pride and ran the way he had to. He almost ran it too conservatively, I think, but what he did was what he had to do.

WCI: would you consider yourself a perfectionist, even though you admit that you and everyone else make mistakes?

ELLIOTT: To the highest degree. I’m pretty bad in that respect. I expect things done a certain way and I won’t accept anything less. I think I’ve gotten better over the past year about getting so ill or angry over things that haven’t been accomplished. At least, I hope I have. But nonetheless, I think in order to be successful I think you have to be a perfectionist in this business. One of two things will happen if you’re a perfectionist: You’ll either get better or you’ll burn out.

WCI: Have you ever reached the point where you thought you might be burned out?

ELLIOTT: Yeah, in 1986. I thought I was. That’s when I got sick so bad with mononucleosis. It started at Daytona. I was pretty much out the whole year. It bothered me in 1987 and again in 1988. Even some last year. I know physically I’m not 100 percent. It’s very hard to get over any illness quickly in this business because the schedule is so tough. It got so bad for me I couldn’t sleep and my eyesight was going bad. For weeks I couldn’t do anything but crawl to the bathroom. Long hours and stress; overwork and the like did it. Not enough rest, not enough exercise and bad diet, too. We’re all part of that with the schedule we have. You’re in one climate and condition one week and the next week you’re in a climate and condition that’s 180 degrees different.

WCI: Are you doing anything differently to keep your health intact?

ELLIOTT: I’m exercising a little more and I’m trying to eat a balanced diet.

WCI: What’s your relationship with NASCAR? How would you describe it?

ELLIOTT: Good and bad. I think for the most part, it’s good. We have our differences, I guess one thing I’ve done is when we’ve had our differences, they’ve know it, if you know what I mean. In 1985 and ’86 we sort of didn’t develop the best relationship. When we ran so well in 1985, it caused a lot of problems between us as you might guess. But since then we’ve come to terms. I do things a bit differently and so does NASCAR. In the last two or three years, it has gotten better about the way it does things. Overall, in its defense, I think NASCAR does a good job with the circumstance in which it has to work. When you talk about going to a track and having to police 40 cars for a race and 60 to qualify, that’s a pretty difficult chore. I’ve been critical of NASCAR before and sometimes it wasn’t justified. At times it was simply trying to do the best it could. I think NASCAR is objective about what it is doing. The proof is in the pudding. NASCAR has the best series and the best attendance. If you look at it from a success standpoint, NASCAR knows what it is doing. If you really, really don’t like what it is doing, the best thing is to not be here.

Now, there are a lot of situations I don’t like and I won’t name them. Of course, there’s a lot all of us don’t like about a lot of different things. The difference in me now from five years ago is that five years ago I probably wouldn’t have accepted that. Now I don’t worry about it. Today, I simply look at it this way: With what NASCAR has to work with, it does a pretty good job. It would be very difficult for anyone to come in and run the Winston Cup Series any better than NASCAR has.

WCI: How is the relationship between you and Bill today, after all the changes that have taken place over the years?

ELLIOTT: We’re still close. I think we’re much more level-headed now about business decisions. Early on, we drew a lot on emotion. The older you get you draw more on experience and less on emotion.

WCI: Have you always been content to remain in the background while Bill was in the spotlight?

ELLIOTT: It doesn’t bother me at all. I never think about that. I know there are a lot of situations where people want attention in that respect, but I can honestly say that it doesn’t bother me. If a good driver does his job and earns $2 million a year, hey, that is fine with me. He can have every cent of it as far as I’m concerned. A driver is a key ingredient. And today, we almost have more good cars than good drivers. So I think we’re fortunate to have a driver like Bill. So if he’s out in front, I have no problem with it. As I said, it doesn’t bother me at all.